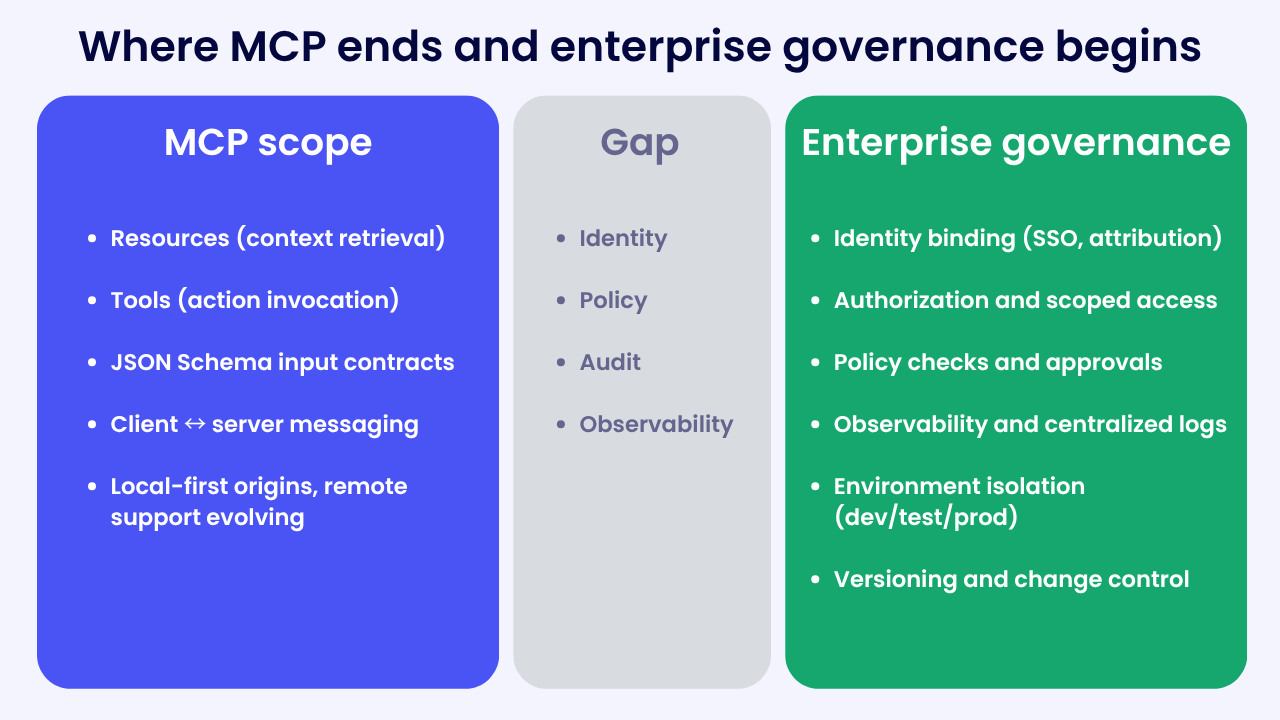

Enterprise teams are talking about the Model Context Protocol (MCP) because it promises a consistent way for LLM-powered agents and copilots to interface with external systems, find context, and call tools across a company’s stack. That can reduce bespoke integrations and speed up proofs of concept. But there’s a gap holding MCP back from enterprise use. And that gap is governance.

MCP describes how clients and servers exchange resources and tools. It does not define who gets to act, when they can act, and under what conditions. For enterprises, that becomes a security and observability problem as soon as agents start touching important systems.

What MCP covers, and what it leaves to you

MCP focuses on two things that matter to agents: discovering and retrieving context from third-party systems, and invoking tools to take action. Inputs are often defined with JSON Schema, which helps teams agree on shape and validation. This is why prototypes move quickly in clients like Claude Desktop or Cursor. MCP helps agents find and use context that LLMs already read.

What MCP does not provide is a native governance framework for policy, authorization, and audit. A newer authorization model exists, which is progress, but client and server support is still uneven and changing.

Think of where API programs landed a decade ago. REST made integration simpler, but enterprises still needed API management to standardize auth, rate limits, catalogs, and analytics. MCP is in a similar place for agents: the interface is helpful, but large organizations still need a layer for identity, policy, visibility, and security.

Where enterprise MCP security breaks down

Questions show up as soon as experiments reach systems that matter.

Who approved the server?

Which identity runs which tool and with what scope?

Where does sensitive data flow?

How are roles and permissions enforced and audited?

Where do logs live, who can see them, and how is usage monitored?

How are credentials validated, rotated, or revoked?

So what does that mean in practice?

- Reviews take longer because ownership is unclear

- Incident response is slower because teams cannot answer who did what and when

- Risk assessments get blocked because scopes are broad and revocation is manual

- Good pilots stall at the hand-off from a developer’s laptop to a shared environment

MCP began local-first. Remote operation is improving, but enterprises need central policy, isolation across environments, and audit as defaults.

Shadow MCP is a governance issue

Many teams want to adopt MCP because it shortens the path to working demos. While that speed is useful for learning, it also creates predictable patterns, some of which have security implications: local servers created by individuals, broad service accounts that blend read and write, logging that lives on a single machine, and no central view. This is what we mean by “shadow MCP.” It’s “shadow IT” for the agent era, and it’s what happens when teams bypass formal channels to move faster. Without a clear path from sandbox to oversight, those quick experiments become unmanaged systems touching real data.

Here’s a concrete example: an engineer connects an agent to a help desk and a document store to draft replies. It works well in a dev environment, so the team shares the local server with others. Soon, multiple agents rely on a single untracked configuration, and logs are spread across laptops. Nothing malicious occurs, but when a permission change breaks a tool, no one can quickly see which agents were affected or roll back with confidence. This is the problem. There’s a lack of a shared path to govern this “experiment”.

What a governance layer should record

If MCP is going to read sensitive data or trigger actions, treat it like any interface that can change a system of record. You should record:

- Caller identity and session context so every action is attributable

- Tool name, version, and schema so contracts are explicit and versioned

- Inputs, target account, and outcome so reviews and audits are possible

- Policy evaluation and approvals so you can prove what was checked and enforced

These are the fundamentals of visibility and control. The next step is putting them into practice without slowing teams down.

Deployment patterns that reduce risk without stalling teams

In early discovery, local development makes sense. That means keeping credentials temporary and avoiding sensitive systems. But when work needs to be shared, you can move to managed remote servers with clear ownership and isolation across dev, test, and prod, tied to corporate identity and tracked configuration.

At a broader scale, a gateway pattern helps. Here’s what that looks like:

- Route agent traffic through a controlled entry point where identity binding, scoped access, allowlists, and logging are enforced

- Keep a small, approved catalog of tools with stable schemas

- Let low-risk reads and drafts run on their own

- Ask for approval when the stakes are higher

- Start with read-only access to lower-risk systems and expand as telemetry proves out.

This keeps builders moving and gives security and IT the signals they need.

Change control for tools and resources

In MCP, tools and resources are meant to look simple to the client, and that is by design. The risk is not that models cannot adapt. It’s unreviewed interface changes underneath running agents that you cannot trace or roll back.

Treat tool definitions like API contracts. In other words:

- Version everything. Keep a clear v1 → v2 lineage for tool schemas and resource shapes. Do not reuse versions for breaking changes.

- Stage changes. Use a test environment and a small set of agents before broad rollout. Record which agents consume which versions.

- Protect consumers. Prefer additive changes. Defer removals. When removal is necessary, publish a deprecation window and a migration note.

- Review like code. Run changes through the same review path you use for API changes. Capture who approved and when.

- Keep rollback simple. Keep a documented, fast rollback path so support teams can recover quickly.

Example: your create_ticket tool adds a new required priority field. If that ships as a silent change to v1, older agents will fail in unpredictable ways. A safer path is v2 with a defaulting rule in the gateway and a short migration plan for any agents that must set priority explicitly.

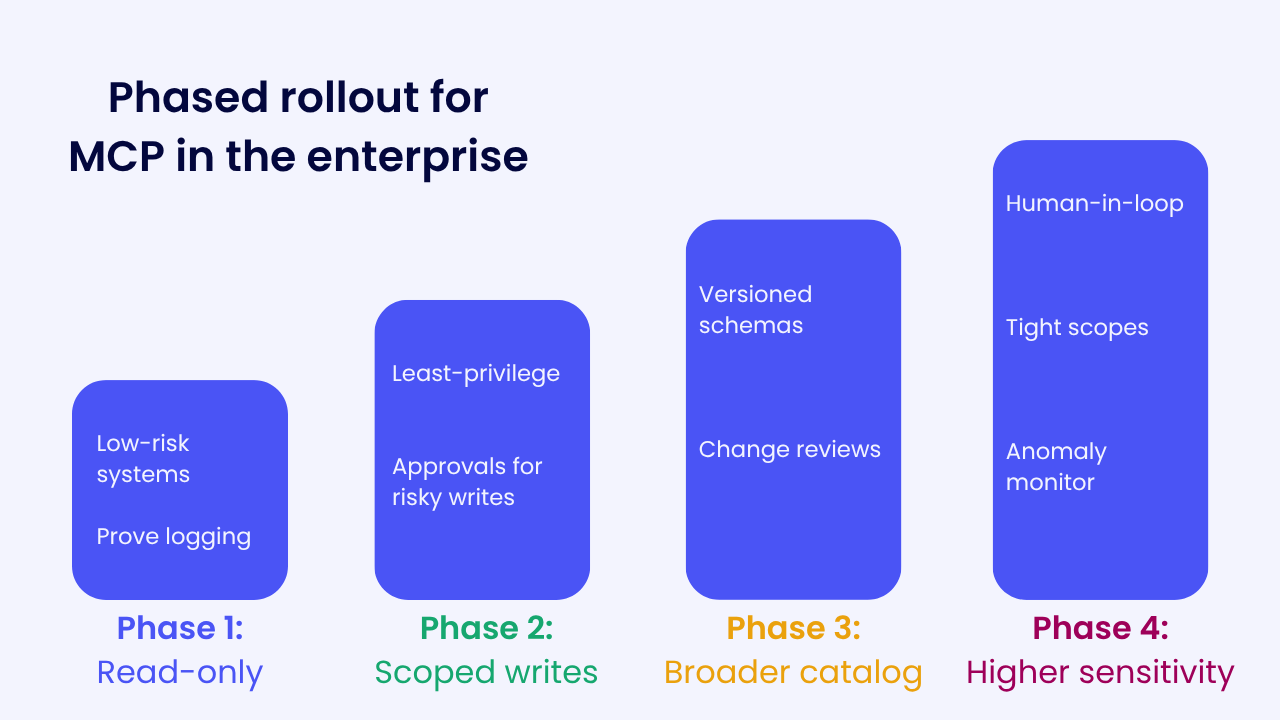

A phased path from sandbox to governed use

When it comes to enterprise security, it’s best to roll things out in phases, and to have an exit plan in place. So for MCP, your phased approach could look like this:

Phase 1: Read-only discovery.

Limit to low-risk systems. Goal is learning and proving logging works. Exit when you can answer “who did what and when” from a single place.

Phase 2: Scoped writes in non-critical systems.

Introduce least-privilege scopes. Add human approval for writes that change customer data, permissions, or financial state. Exit when you can demonstrate clean traces for successful writes and for denied writes.

Phase 3: Broader catalog, stricter policy.

Expand the approved tool list. Enforce schema versions. Require change reviews. Exit when you have a weekly review of MCP activity with owners and a working rollback plan that has been tested.

Phase 4: Higher-sensitivity systems.

Keep human-in-the-loop for high-risk actions. Tighten scopes and monitor anomalies. Exit when incident response can trace and contain an MCP-driven action within minutes.

At every phase, keep the same two questions in front of the team: can we see what happened, and can we change the outcome next time.

What the new authorization spec changes

The newer authorization model introduces capability-style permissions and session handling. On paper, that makes scoping and revocation more precise. In practice, enterprise value depends on end-to-end support across clients and servers.

So here’s what you can do now:

- Map capabilities to roles. Define which capabilities align to your existing roles and scopes. Keep a short matrix of “role → allowed tools.”

- Test client behavior. Build a simple support matrix that shows which MCP clients you use and which parts of the authorization model they actually honor.

- Prefer short-lived sessions. Where supported, prefer short sessions with clear renewal to reduce the blast radius of leaked credentials.

- Keep fallbacks. Assume uneven support. Your governance layer should still enforce identity, scopes, and logging even when a client does not.

- Review updates regularly. Specs and implementations are moving quickly. Revisit your matrix on a set cadence so policy does not drift from reality.

Until adoption is consistent, treat MCP usage that touches critical systems as experimental and rely on your governance layer to carry the load.

Questions to ask your team now

Ownership

- Which MCP servers exist today and who owns each one?

- Where does the configuration live and how are changes reviewed?

Access

- Which tools have write access and what scopes do they use?

- How are identities bound to tools and how does revocation work?

Telemetry

- Where do logs live and can you answer who did what, when, with which inputs, and what was the outcome?

- How are anomalies detected and reviewed?

Change control

- How are tool schemas versioned, who approves changes, and how are rollbacks performed?

- Which agents are on which tool versions?

Incident response

- How would you contain a mis-scoped tool or leaked credential within minutes?

- How would you notify downstream owners and verify resolution?

Readiness

- What must be true before MCP connects to a higher-sensitivity system?

- When was the last end-to-end test of approvals, logging, and rollback run?

If any of these answers require hunting across laptops or DMs, start by centralizing ownership, logging, and the tool catalog.

MCP’s bottom line

MCP’s promise is real, but the governance gap is real too. Keep experimentation moving, and pair it with a clear governance layer before agents touch systems of record. Standards will keep moving. Your policies, logs, approvals, and rollback paths should stay steady.

If you want to see a gateway model in practice, watch our session on MCP governance and Tray Agent Gateway where we walk through examples and take questions.